EMILY BRONTË: A THEORY

By Sarah Fermi

Keywords: Emily Brontë, Robert Clayton (of Haworth)

Why did Emily Jane Brontë write Wuthering Heights? And how was she able to do it? In

spite of the massive amount of material published about the Brontë sisters over the past

one hundred and fifty years, these two questions still remain unanswered. Yet given the

autobiographical nature of much of the material in the novels of Charlotte and Anne

Brontë, it is almost unthinkable that Emily would not also have used her own experience

in the creation of her great book. How could she write so vividly about love, grief, and

hatred without having known these emotions in her own life?

Many Brontë biographers have puzzled over these questions, and some have even

suggested as a possible answer that Emily had a serious romantic attachment at some

point in her life, but they have been daunted by the scarcity of facts about Emily’s life

and left the question open.1 In his A Life of Emily Brontë Edward Chitham has gone a

step further and proposed a possible relationship with an offspring of the Heaton family

— the child of Elizabeth Heaton and John Bakes. The suggestion that perhaps the object

of Emily’s affections was connected with the Heatons of Ponden, an old local family well

known to the Brontës, whose home, Ponden House, certainly appears to be connected

with Wuthering Heights, seemed to be very promising.

This was the starting point of a quest which brought me to the West Yorkshire

Archives in Bradford in the spring of 1989. One afternoon’s research there with the

Heaton Papers quickly dispelled this hope — the child in question was little Eliza

Matilda Bakes, who died in 1817 aged two, and is buried with her mother in Haworth

churchyard. Nevertheless, the idea of an early love interest in Emily’s life struck me as

worth pursuing. For the next few years I worked on learning more about the important

Haworth families, particularly the Heatons, and also the most significant local family,

the Greenwoods. In parallel with this study, I learned all I could about Emily, and

carefully examined the chronological development of her poetry.

There are quite a few aspects of her life which present interesting questions. Why did Emily change from a charming and outgoing child to a solitary and reserved young woman? Why was she sent away to Roe Head School in 1835 at the relatively advanced age of 17, for what

appears to be no good reason, and when Mr Brontë’s finances were likely to be stretched

by the plan to send Branwell to the Royal Academy Schools? Why did he write a warning

letter to his old friend, Mrs Franks, hinting at possible trouble ahead? What was the

real reason for Emily’s near-fatal illness at Roe Head? Why is there a striking change in

the tone of her poetry between 1836 and 1837? It occurred to me that all these questions

could be answered if one assumed the following theory:

1) When Charlotte goes away to Roe Head School in January 1831, Emily and Anne

begin to create their own private world of Gondal, which they act out on the moors.

2) They enlist the help of a local boy to play with them.

3) This boy is working-class and therefore an unsuitable playmate, and the meetings

are kept a secret from Mr Brontë and Aunt Branwell. A romance develops.

4) The secret is somehow discovered in the summer of 1835, and Emily is sent off to

Roe Head School to break up the relationship between her and the young man. The

collapse of Emily’s health, requiring her return home, is partly due to her despair at

this separation from the young man.

5) In the winter of 1836–37 the young man dies, leaving Emily deeply affected. Her

poetry strongly suggests that she experienced a traumatic event at this time: all the

poems of 1836 (the earliest that exist) are cheerful or thoughtful, or, in one case,

exuberant. There are no poems in January, 1837, and in February she begins, almost

obsessively, to write poetry about death, grief, and nightmare.

Using this rudimentary theory as a beginning, I then examined the Haworth Parish

Records to see if, in fact, there had been a working-class lad who died at the suggested

time. I found one candidate: Robert Clayton. He was the second son of a local weaver,

Nathan Clayton. Robert was born in July 1818, the same month and year as Emily, and

he died in December 1836.

I also learned that there once existed a group of letters

from Emily Brontë in the possession of a lady named Fanny Clayton, but which were

destroyed many years ago. Sadly, I was unable to learn any more about these letters.

However, I did discover many interesting bits of information relating to the Clayton

family. They were descendents of an important (and persecuted) Quaker family, stalwarts

of the Stanbury Quaker Meeting in the seventeenth century. At the time of the

Brontës, the Claytons were friendly with the Heatons of Ponden, a fact evidenced by

their inclusion in lists of friends invited to several Heaton family funerals. Robert and his

family lived for some time at Far Slack, an old house on the edge of the moors across the

valley of Ponden Beck from Ponden House. The family moved away from the area

shortly after Robert’s death, but returned to Haworth about 1842. One of the most

suggestive facts I uncovered was the death of Robert’s older brother, John, in May

1833. Emily wrote two poems, both of which concern two deaths: the first, written

19 December 1839, reads:

Heaven’s glory shone where he was laid

In life’s decline.

I turned me from that young saint’s bed

To gaze on thine.

It was a summer day that saw

His spirit’s flight;

Thine parted in a time of awe,

A winter-night.

The other poem is the strange and beautiful ‘Death that struck when I was most

confiding. . .’ written in April 1845, which also speaks, albeit metaphorically, of two

deaths — one which barely moved her (‘little mourned I. . .’), and a second which ruined

her life (‘Time for me must never blossom more. . .’). It is possible that both of these poems

refer to the deaths of John in late spring, 1833, and then Robert in mid-December, 1836.

Finally, there is one tiny piece of possible documentary evidence for the connection

between Emily and Robert: the Gondal poem ‘Heavy hangs the raindrop. . .’, written in

May 1845, about a ‘melancholy boy’, is accompanied by the initials A.E. and R.C.

The first set is very likely to stand for Alexander Elbë, an early character in the Gondal

stories (who is already dead before Emily and Anne begin to write these stories down

in about 1837), and the second set is, perhaps, for Robert Clayton, who, in my theory,

played the part of Alexander Elbë in the girls’ early Gondal games on the moors. Emily

wrote two of her sad early poems (March and August 1837) about the death of

Alexander Elbë and she returned to the subject again in December 1844. The initials

R.C. do not correspond to any known Gondal character.

My research into another local family, the Greenwoods of Bridgehouse, Springhead,

and Woodlands, has suggested an addition to the theory. It seemed to me highly likely

that when Emily was sent home from Roe Head after less than three months, Aunt

Branwell might well have considered it her duty to find a more respectable suitor for

Emily. A close friend of Patrick Brontë’s, Joseph Greenwood, Esq., of Springhead, had

three daughters exactly the same ages as Charlotte, Emily, and Anne (and there is

written evidence that the girls were friendly) and, as it happens, he also had two eligible

sons, William and James, several years older than the girls. This is all very speculative,

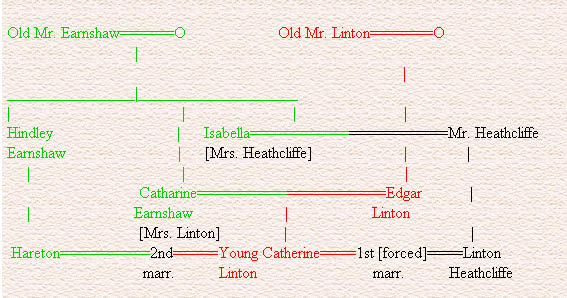

but the parallel between a Greenwood boy and Edgar Linton, Catherine Earnshaw’s

suitor in Wuthering Heights, seemed too good to ignore: Joseph Greenwood was, like

Mr Linton, the local magistrate; he was also the Lord of the Manor of Oxenhope. Like

the Lintons, the Greenwoods were at the top of the social tree in the area — marriage to

one of the boys would be a big step up the social ladder for the Brontës. In my theory,

Emily is courted by young James Greenwood, and for a few months she enjoys his

attentions. But when Robert Clayton learns of her betrayal, he is deeply hurt and in

his despair he dies in a careless accident on the moors in the winter of 1836. Robert’s

death puts paid to any ideas Emily might have had of ‘marrying up’; she feels partly

responsible for his death and is left with life-long feelings of guilt and isolation.

Because I am not able to prove this theory beyond the circumstantial evidence

outlined above, I have never tried to publish it as conventional ‘academic’ paper. But I

thought it would be interesting to see if the story could be told in another form, so

several years ago I suggested this theory to the BBC with the idea that it would make an

intriguing drama-cum-documentary. The producers were enthusiastic, but decided it

would work best as straight drama. They obtained development funds for the idea, and

the services of a well-known screen writer to write the script — Sally Wainwright, whose

television drama ‘Sparkhouse’ was loosely based on Wuthering Heights. Sally has

written a dramatic and moving script, but unfortunately it was not commissioned for

production, though its time may yet come.

Since then I have written a fictionalized biography of Emily Brontë in the form of her

own private journal; this work includes not only the theory outlined above, which covers

the years 1831 to 1837, but also Emily’s life after Robert’s death right up to her own

death in 1848.

My theory is unlikely to be true in every detail, but I believe that something very like

it must have happened. I have found nothing to contradict the speculative sequence of

events outlined above, and the discovery of Robert and John Clayton, whose deaths ma

have been obliquely recorded in Emily Brontë’s poetry, seems to me to confirm the original

idea, and perhaps bring us a step closer to an answer to the questions of how and

why Emily Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights.

BBC Radio has published the play

Cold in the Earth and Fifteen Wild Decembers

By Sally Wainwright, based on a theory by Sarah Fermi.

Why did Emily Jane Bronte write Wuthering Heights? And how was she able to do it? In spite of the massive amount of material published about the Brontë sisters over the last 150 years, these two questions still remain unanswered. Yet given the large amount of autobiographical material in the novels of Charlotte and Anne Bronte, it is almost unthinkable that Emily would not have also used her own experience in the creation of her great book. How could she write so vividly about love, grief and hatred without having known these emotions in her own life?

This is a compelling drama about the story of Emily Bronte's socially transgressive love affair with a weaver's son.

'Heathcliff had knelt on one knee to embrace her; he attempted to rise, but she seized his hair, and kept him down.

'Heathcliff had knelt on one knee to embrace her; he attempted to rise, but she seized his hair, and kept him down.

The old church, Haworth.

The old church, Haworth.

The Brontë sisters (Anne, Emily and Charlotte, aged about 15, 17 and 19 respectively) painted by Branwell in 1834

The Brontë sisters (Anne, Emily and Charlotte, aged about 15, 17 and 19 respectively) painted by Branwell in 1834

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

(1777-1861)

(1777-1861) Revs. Andrew Harshaw and Thomas Tighe. In October 1802 Patrick Brontë, aged 25, registered as a student at St John's College Cambridge. He corrected the spelling of his name from Brunty to Brontë. It is not known for certain why he did this, he may have wished to hide his humble origins. Why Brontë? He would have been familiar with classical Greek and may have chosen the name after the Greek mythological god "Bronte" which translates as "thunder". Another theory is that in 1799 King Ferdinand of Naples bestowed the honour of Duke of Bronte in Sicily to Lord Nelson for fighting off the French Navy. Patrick may have taken the name as respect of Lord Nelson. His time at college, although financially difficult , was successful, and as a scholar he was always in the top group academically. He graduated in April 1806 with a Bachelor of Arts degree and then paid a visit to his family in Northern Ireland. He returned to England and never visited Ireland again.

Revs. Andrew Harshaw and Thomas Tighe. In October 1802 Patrick Brontë, aged 25, registered as a student at St John's College Cambridge. He corrected the spelling of his name from Brunty to Brontë. It is not known for certain why he did this, he may have wished to hide his humble origins. Why Brontë? He would have been familiar with classical Greek and may have chosen the name after the Greek mythological god "Bronte" which translates as "thunder". Another theory is that in 1799 King Ferdinand of Naples bestowed the honour of Duke of Bronte in Sicily to Lord Nelson for fighting off the French Navy. Patrick may have taken the name as respect of Lord Nelson. His time at college, although financially difficult , was successful, and as a scholar he was always in the top group academically. He graduated in April 1806 with a Bachelor of Arts degree and then paid a visit to his family in Northern Ireland. He returned to England and never visited Ireland again.

Maria Branwell was the daughter of Thomas and Anne Branwell of

Maria Branwell was the daughter of Thomas and Anne Branwell of